"Don’t ask me what I have done on matters of business … The only person I am going to see within the next 36 hours is Jesse Jones."

President Franklin Roosevelt, July 16, 1933

“He has allocated and loaned more money to various institutions and enterprises than any other man in the history of the world.”

Vice-President John Nance Garner, October 31, 1936

“In all the U.S. today there is only one man whose power is greater: Franklin Roosevelt… The President knows Congress will give more to Jones without debate than he can get after a fight… Emperor Jones is the greatest lender of all time.”

TIME magazine, January 13, 1941

Courtesy Campbell Photo Service. (left to right) Edith Wilson, Mary Gibbs Jones, and Jesse Jones.

Courtesy Northmore—Detroit Times. Jesse Jones and Will Rogers. Jesse Jones (front row, second from left) and President Herbert Hoover (center), 1932.

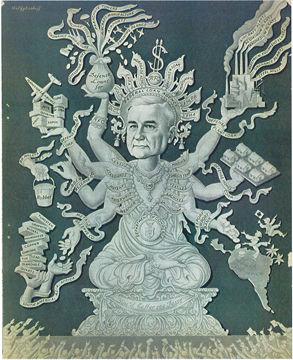

Courtesy Library of Congress. Jesse Jones, President-elect Franklin Roosevelt and then Senator Cordell Hull of Tennessee. In a rare instance, Roosevelt's leg braces are visible in the picure. Courtesy Corbis. (left to right) Mariette Garner, Vice President John Nance Garner, the Joneses, and Edith Wilson celebrate Jesse Jones's sixty-third birthday. Howard Hughes and Jesse Jones leave the State Department building on July 21, 1938, after Hughes met with Secretary of State Cordell Hull to thank him for the State Department's assistance with his record-breaking around-the-world flight. Courtesy Corbis. Jesse Jones is sworn in as Secretary of Commerce on September 19, 1940, by Associate Supreme Court Justice Stanley Reed, who was formerly the RFC's general counsel. Courtesy Corbis. A 1941 Fortune magazine cover story featured Jesse Jones as an omnipotent deity.

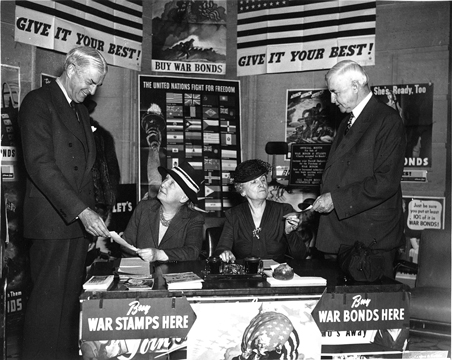

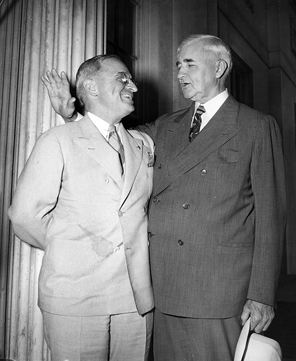

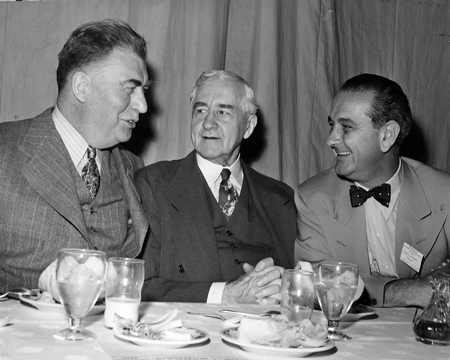

Courtesy Fortune, PARS International. Captain Eddie Rickenbacker, Eastern Airlines president and a celebrated World War I pilot, shakes hands with Orville Wright at the 1943 dinner arranged by Jesse Jones to honor the fortieth anniversary of the first Wright Brothers' flight, and to announce the return of the Kitty Hawk from England. Courtesy AP/Wide World. Susan Vaughn Clayton and Mary Gibbs Jones, who sold war bonds from a desk in the RFC building's lobby, sell bonds to their husbands, Will Clayton (left) and Jesse Jones. President Harry Truman and Jesse Jones. Courtesy AP/Wide World. President Dwight Eisenhower, Mary Gibbs Jones, Mamie Eisenhower and Jesse Jones. (left to right) Senator Edwin C. Johnson of Colorado, Jesse Jones, and Senator Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas. Courtesy Houston Chronicle.

Jesse Jones was born in 1874 on his father’s prosperous Tennessee tobacco farm and found himself in the midst of Houston’s civic and business leadership when he moved to town in 1898 at the age of 24 to manage his late uncle M. T. Jones’s estate of timberland, sawmills and lumberyards. Houston’s leaders were simultaneously building their businesses as well as the organizations and infrastructure that would serve people, enhance life and spur growth in their town of 40,000. They knew they would prosper only if their community flourished. Jesse Jones embraced their combination of capitalism and public service from the time he stepped off the train to start his new life in Houston. Within four years of his arrival in Houston, Jones started his own lumber business, invested in local banks and began developing streets in today’s Midtown where he built and sold small homes. By 1908, he was building Houston’s first skyscrapers, each ten floors tall.

Monumental changes were happening in Houston. While Jesse Jones was building the city’s tallest buildings, Congressman Tom Ball was busy in Washington, D.C., convincing the United States Congress to pay half the cost of developing the Houston Ship Channel. The proposal to share costs between a municipality and the federal government for a major infrastructure project was unprecedented, but the city’s civic and business leaders, including Jones, knew they had to step up: Houston’s growth would be sharply limited without access to the sea. Congress agreed to the “Houston Plan,” and within 24 hours Jones persuaded his fellow bankers to join him in buying the bonds needed to pay Houston’s half of the cost. Jones was appointed as the Houston Harbor Board’s first chairman and oversaw the construction of the warehouses, docks and piers that would welcome the first ships to arrive from around the world in the Port of Houston in 1914. He experienced firsthand the power of partnering with the federal government. His success captured the attention of President Woodrow Wilson, who wanted people in his administration to invigorate the neglected southern and western United States. Like Jones, he saw government as a positive agent for progress.

Wilson invited Jones to join his administration in different capacities including secretary of the treasury, but Jones repeatedly declined the president’s requests so he could concentrate on building Houston and his businesses. When the United States entered World War I in 1917, however, Jones agreed to Wilson’s request to head the Department of Military Relief (DMR), one of two major divisions of the American Red Cross; by presidential designation, the Red Cross was the official medical and disaster relief agency assigned to assist citizens and soldiers in the United States and Europe. Jones was one of the original investors in Humble Oil Company—now ExxonMobil—and he sold his stock to finance his trip and to sustain his businesses during his absence.

Jones and the DMR recruited and trained thousands of nurses and doctors for service on Europe’s battlefields. The DMR organized ambulance networks and built field hospitals to treat the wounded and operated canteens throughout Europe to provide respite for exhausted soldiers. In the United States, the DMR built the nation’s first rehabilitation centers to treat disabled veterans and help soldiers return to their homes. Publications called Jones “Big brother to four million men in khaki,” and he also became “big brother” to Army nurses when he lobbied President Wilson in 1918 to give them official military rank. Jones wrote to Wilson, “The standing of the profession of trained nurse, and particularly of the Army nurse, should be so raised, socially and otherwise, as to attract the very best class of women who go in for professional careers, such as teaching, medicine and law.”

Once his overseas missions were complete, Jones returned to Houston, where he embarked on the most ambitious phase of his building career, dove into Democratic national politics and in 1920 married Mary Gibbs Jones. Jones was a multi-tasker. Even as he opened Houston’s fanciest theaters, its most lavish hotels and its tallest office buildings—while simultaneously operating the city’s largest bank and newspaper—he put up significant buildings in New York City, Fort Worth and Dallas. On top of that, he was the Democratic National Committee’s finance chairman. Called the Democratic Party’s “miracle man,” he erased its persistent and debilitating debt and captured the 1928 national convention for Houston, the first to be held in the south since before the Civil War and one of the first to be widely received over radio. The convention put Houston on the map and Jesse Jones in the spotlight.

In a matter of months, Jones built a convention hall big enough to accommodate the 25,000 conventioneers who were about to pour into a town of 300,000. While walking to the convention center, most likely from one of Jones’s hotels, the visitors couldn’t help but notice the soaring skyscraper under construction since it stuck out in the sky above everything else. Jones’s 35-floor Art Deco style Gulf Building—now the Chase Bank Building—would be Houston’s tallest building until the 44-floor Humble Oil Company Building opened in 1963.

The Gulf Building opened in August 1929, just months before the stock market crash ushered in the Great Depression. At first Houston was buffered from the worst of the catastrophe because commerce continued in oil, cotton, lumber and the Port, but by 1931 two banks were about to collapse. Jones knew if those failed, more banks would fall like dominoes not only in Houston, but across Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas and Oklahoma, since small rural banks kept their reserves in those large urban banks that were teetering on the edge. Jones called Houston’s bankers and business leaders to a meeting and proposed a rescue of the two banks. He met fierce opposition from those who argued that the banks had been terribly mismanaged. After 72 hours of contentious meetings, Jones brought in Captain James A. Baker—a major stockholder in one of Houston’s largest banks and the grandfather of former Secretary of State James Baker—to back his rescue plan, and it prevailed. As a result of Jesse Jones’s farsighted leadership, no bank in Houston failed during the Great Depression. In a letter to one of the holdouts who had finally relented, Jones wrote, “I believe that all we have done, are doing, and must continue doing, is necessary for the general welfare, and we cannot escape being our brother’s keeper.”

Just as Jones’s success with the Houston Ship Channel had caught Woodrow Wilson’s attention, his success with Houston’s banks appealed to President Herbert Hoover, who was fighting the nation’s economic collapse primarily by promoting voluntary humanitarian action. So far, that had not worked. By 1932, 25 percent of the workforce was unemployed; gross national product had plunged by half; stocks had lost 75 percent of their value; and thousands of banks had failed with more continuing to go under. Everyone was desperate and afraid. As a last-ditch effort, President Hoover established the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) to provide government credit beyond what was privately available to banks, railroads and insurance companies, particularly those on the brink of bankruptcy. He hoped the RFC support would restore confidence in those institutions and halt the downward spiral. Seeing Jones’s leadership in Houston, Hoover asked him to join the RFC’s bipartisan board. Thus, the Joneses moved to Washington, D.C., where they would live for the next 14 years.

President Franklin Roosevelt was elected later that year. Within five days of his 1933 inauguration, he and the United States Congress had expanded the RFC’s power and soon after made Jesse Jones its chairman. New legislation allowed Jones and the RFC to purchase preferred stock in banks, supplying them with ready money to lend in hopes that doing so would get the frozen wheels of the economy to turn again—but the shell-shocked bankers hoarded the money instead. With no other option, Jones and the federal government’s RFC stepped in as the lenders of last resort.

Throughout the Great Depression, Jones and the RFC judiciously loaned billions of dollars to applicants seeking help. Those loans saved homes, farms, businesses, banks and railroads. They extended aid to disaster victims. They helped develop the latest in high-speed trains and built aqueducts, tunnels and bridges. Government loans even financed the purchase of toasters, water pumps, refrigerators, radios and fans for people in rural areas after the RFC’s Rural Electrification Administration brought electricity to their homes. Remarkably, these enormous efforts to build infrastructure, to nurture innovation, to boost employment and to financially rescue people and businesses during the nation’s most severe economic collapse made money for the federal government and its taxpayers as the loans and the interest on them were steadily repaid.

The government’s purchase of preferred stock in banks was the essential first step to this great effort to restore the economy. As Jones explained in 1936, “Rebuilding the banks was like putting a new foundation under the house. It was absolutely necessary to prevent the house from falling down.” Some economists and politicians came to recognize that wisdom. The Troubled Asset Relief Program, also known as TARP, which was initiated during the “Great Recession” of 2008 and was a major factor in the country’s recovery, was modeled on Jones’s earlier “Bank Repair Program.”

By 1936, the RFC had become the world’s largest bank and its biggest corporation, and Jesse Jones with steadying moderation held the reins. During a national radio broadcast at a banquet in Jones’s honor, Vice President John Nance Garner said about his friend and fellow Texan, “He has allocated and loaned more money to various institutions and enterprises than any other man in the history of the world.” The Saturday Evening Post wrote about Jones, “Next to the President, no man in the Government and probably in the United States wields greater powers.” Similarly, in Jones’s second TIME magazine cover story, the reporter wrote, “In all the U.S. today there is only one man whose power is greater: Franklin Roosevelt.”

Anticipating world war, Jones and Roosevelt converted the RFC’s focus from domestic economics to global defense. At the time, 17 nations had armies larger than the United States. The German military budget was 20 times larger. Japan had 7,700 airplanes; the U.S. had only 2,500, and most of them were obsolete. To make matters worse, President Roosevelt’s hands were tied from neutrality acts and polls showing 80 percent of the respondents opposed participating in the European conflict unless the United States was directly attacked. Rather than fighting with Congress and inflaming the public, President Roosevelt turned to Jones and the RFC to begin militarizing industry almost two years before the attacks on Pearl Harbor. The RFC’s actions during World War II would overshadow its monumental contributions during the Great Depression.

In 1940, Jones and the RFC began converting existing plants and building massive new ones to manufacture the airplanes, ships, tanks and trucks required to fight and win World War II. The RFC also built enormous mines and plants to produce steel, magnesium and aluminum, and it constructed the first tin smelter in the United States. In addition, Jones recruited Houstonian and bridge partner Will Clayton to procure strategic materials and minerals from around the world. At almost miraculous speed, the RFC developed synthetic rubber, moving from the lab to mass production in a matter of months, just as the Japanese took over the country’s main source of natural rubber in the Pacific. Without the RFC initiative and investment to develop this vital alternative resource, the Allied Forces might have been stuck in place and unable to fight. The New York Times reported after the war that the synthetic rubber initiative was “exceeded in magnitude only by the atomic energy program.”

Even so, the RFC’s largest wartime investment was in aviation. As Jones explained to audiences during one of his many reassuring national radio addresses, “We have built and own 521 plants for the production of aircraft, aircraft engines, parts and accessories… this is ten times the value of privately-owned investments in this industry.”

TIME magazine observed about Jones’s public comments, “Not J.P. Morgan, not even Franklin Roosevelt could be of as much comfort to the public. To many a U.S. citizen, great or small, if Jesse Jones says O.K., O.K.” In his years leading the RFC, almost everyone had seen him countless times in magazines, newsreels and newspapers or had heard him over the radio. Because of his record and his reassuring personality and presence, most Americans simply called him “Uncle Jess.”

Finally, the war ended, and the Joneses returned to Houston, where they focused on philanthropy, having established Houston Endowment in 1937 to improve life for the people of Houston. After their return, they began to transfer their buildings and businesses to the Foundation. Education was key to the Joneses. Mary had attended college when it was rare for women to do so, and Jesse, who had quit school after the eighth grade, often said he felt handicapped by his lack of education despite his singular success. Consequently, through Houston Endowment the couple established large college scholarship programs at universities throughout Texas and made a point of dividing them equally between men and women. Even more rare for the 1940s, a time of racial segregation, the Joneses established large scholarship programs for minority students. One of the largest grants made before Jesse Jones passed away in 1956 and Mary died in 1962, went to build the Mary Gibbs Jones College at Rice University so women for the first time could live on campus.

More than any other historical figure, Jesse Jones put a stamp on the city’s physical shape, both as Houston’s preeminent developer and the Port’s biggest champion. And as much as the formidable Texas politicians to follow, he served the country in pivotal national roles. He provided emergency medical care to Europe’s battlefields and at home during World War I; he made essential contributions to preserving capitalism during the Great Depression; and helped ensure Allied victory during World War II. In short, he was a significant force in all the major events of the first half of the twentieth century. In addition, he left behind a substantial philanthropic foundation to nurture Houston, the city he loved and called home.

back to top